I recently finished reading an incredible book: Peter Boag’s “Re-Dressing America’s Frontier Past” (2011). It takes an insightful look at the American West of the 19th century with its romantic images of rugged cowboys and frontier life, and shows its way more complicated than we typically imagine. Boag demonstrates (with copious examples) that cross dressing was pervasive in the Old West and it was not uncommon for men or women to cross dress there to redefine their gender and sexual identity.

The reason why this probably is a surprise to many of us (including me) is that these people were very consciously written out of the Western narrative, especially in the wake of Frederick Jackson Turner’s 1893 Frontier Thesis. Consciously and unconsciously, people re-wrote contemporary accounts and later histories of cross dressers to fit the image that we typically associate with the Old West today:

“Deeply held cultural views of the frontier influenced the science of sexology in America at the turn of the nineteenth century, working to remove [Joseph] Lodbell and others like him from America’s mythic frontier history and thus, in an essential way, from the most celebrated and powerful of our national narratives.” (168)

Cross dressing, homosexuality, and a wide range of non-binary sexual orientations and gender identities were no strangers in the Old West. Erasing and distorting their stories preserved the mythical image of the West and helped protect the American national narrative that emerged in this period and still persists to this day:

As Americans grew discomfited by the gender and sexual changes they witnessed, as they became troubled by the passing of the frontier and what they thought that meant, and as they witnessed a remarkable amount of cross-dressers in the West, they began to re-imagine, reinterpret, and redefine both the cross-dresser and the frontier and the West of which s/he was a part…they created elaborate biographies for them, scarcely related to fact, that transformed their transgendered behaviors (and eased suspicions about their sexuality) by explaining these behaviors as merely due to a westering process that, thank goodness, was as ephemeral as the frontier. (194)

Boag’s book features several characters who were originally from Pennsylvania. Without further ado, here’s a short profile of each. The Keystone State and its people have long played an important role in the history of the American West, it shouldn’t surprise us that PA also contributed to its crossdressing past too!

The Springer Daughters

Boag’s survey of nineteenth century American newspapers reveals what he called “the omnipresence of women who dressed as men” in the West. (32) Dressing in masculine clothes could protect women and give them more opportunities for than would normally be afforded them. When cross dressing women were featured in the press, they usually mentioned safety when explaining their choice.

Boag reports that one of the earliest mentions of women wearing men’s clothing in the West comes from an 1851 account in the Lowell Courier. Four daughters of a Philadelphia merchant named Springer were traveling cross country to California. They ran into a bemused “lady correspondent” from the Lowell Courier on a riverboat near Louisville who described their attire as “fashionable gentlemen’s suits.” (33) The Springer daughters planned to keep these clothes as far as Independence, Missouri. There they’d change into rougher men’s clothing they thought was more “suitable” for the wagon ride to the West Coast.

The Springers clearly made an impression on the journalist and she described them in detail: “Their suits worn on the boat were fashionable and fine black dress coats, black pants, buff vests, and hats of glossy black. The buttons of their vests were plain, flat surfaced, and very rich. Their coats and pants were all modish and fit to a nicety. Their hair was cut short, and their whole appearance was very genteel.”

She also reported the Springer daughters were well received by the other passengers. “Their conduct on the boat was perfectly lady-like; indeed, every one was pleased with them…With perfect truth” she admitted, “no harm or ill-nature resulted from the course pursued by the Misses Springer. Every passenger spoke well of them.”

By the end of the journey the Springers had several admirers, including the journalist herself. All the boat’s lady passengers (with “only one exception”) cheerfully admitted that they no longer had any problems with women dressing in men’s clothing. The Courier journalist even confessed she would like to get a handsome suit, “to be worn occasionally in select company.” But she wasn’t keen on black like the Springers were, and instead decided she would prefer a blue dress coat, buff vest, and “drab pantaloons.”

The journalist did issue one warning to her readers though- that women dressing like the Springer daughters were devastatingly charming. “I must caution you not to keep your eyes too intently upon her person, or you will be sure to fall in love with her. She is the the beau ideal of a handsome gentleman, and I could never desire to see her in female dress.”

As they disembarked from the riverboat and said their final farewells, the oldest Springer daughter said a day would come when “all women will wear male attire.” And they were right (to a point). Boag notes women dressing as men were incredibly common in the West up through the 1920s. “And yet regardless of their commonness, they constantly made the news” as if it were something extraordinary. (57)

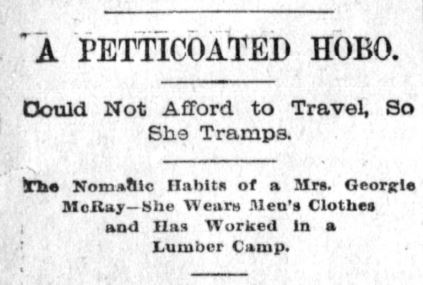

Georgie McRay

Like the Springer Daughters, George McRay was a woman who dressed in masculine clothes to open doors in the West that normally would be closed to women. However, her treatment by the press was strikingly different.

Reporters first encountered her in the office of a humane agent in Kansas City in 1896, and newspaper reports that circulated widely (I’ve seen this same article published in half a dozen papers) zeroed in on her appearance.

McRay was an “ordinary-looking woman” and there was “nothing in the woman’s appearance to attract more than a passing look.” If readers weren’t convinced of her ordinariness by then, the article doubles-down a few lines later: “her face has the peculiar leathery look common to those who are accustomed to facing all weathers, but anyone passing her on the street would at once put her down as the hard working wife of a struggling farmer.” Though she dressed like the other working men in town, the press took pains to make sure their audience knew she was a woman.

There are several other women like McRay that appear in “Re-Dressing America’s Frontier Past.” Boag argues that American society, and the press that wrote about it, believed that a person’s gendered behavior indicated their sexuality. And so cross-dressing raised notable anxiety from observers. Though this view slowly eroded around the turn of the 20th century, it was still present when McRay was interviewed in 1896. “When the mass-circulation press discovered women who dressed as men,” Boag writes, “it typically feminized them, often by focusing on their womanly bodies and appearances once their disguises failed them.” (43).

Georgie McRay was born sometime around 1850 in Centre County, PA. Growing up on a farm, she was expected to do “a man’s work in the field.” Citing her childhood work experiences as the beginning of her cross-dressing habits, reports said she manifested a desire to travel at a young age and headed west. She didn’t have the money to travel comfortably, so she “turned her sinewy hand to almost every kind of labor” to get around. And in order to create more job opportunities for herself, she dressed in men’s clothing from the day she left her family farm.

Working, tramping, and adventuring she made her way across the western United States. Some of her stops included Montana, Wisconsin, Indian Territory, Arkansas, and Missouri, and she worked jobs typically reserved for men in all of them. “She found no difficulty swinging the woodsman’s axe” or keeping the company of “terribly rough” men in her journeys. In several instances, she was arrested for “masquerading” as a man and was coerced to leave town or even forced break out of prison and flee, but even this did not deter her preferences for work or dress.

The reporters interviewing McRay couldn’t seem to understand why she acted the way she did. “[B]ut for her unwomanly nomadic habits she would be an excellent member of the humble society to which she would naturally belong.” She didn’t match the assumed link between “sexuality…behaviors, actions, and appearance” that Boag found in many discussions of cross-dressers in 19th century newspapers. (79)

Seemingly frustrated and confused, the articles describing McRay ended calling her “simply a female hobo whose habit of tramping hither and thither has probably reached the chronic stage, and is probably beyond cure.” She didn’t fit neatly into a binary gender system and the press couldn’t explain why.

But McRay had the last word. When she was asked if she planned on continuing her cross-dressing, nomadic ways, she replied “Why not? I like the life I am now leading, as it gives me a chance to see the country.”

Joseph Lobdell

Of the Pennsylvanians included in Boag’s scholarship, Joseph Israel Lobdell is by far the most well known and his life the best documented.

Lobdell was a “truly a frontiersman‘s frontiersman.” (161). A hunter, trapper, and woodsman originally Delaware County, New York, he was well known in his community and beyond for feats like hunting a panther single handedly at the age of eleven and for bagging 160 deer and 77 bears before he turned twenty.

Unbeknownst to some neighbors, however, Lobdell was born a woman and been named Lucy Ann by his parents. One day while hunting dressed in men’s clothes, he encountered a reporter who published a story on his life and gender identity. It was a shock to many who knew or had heard of his hunting exploits, and before long there were so many curiosity seekers bothering Lobdell that he decided to leave town and start anew in the West.

But before he left, Lobdell wrote an autobiography about his life, “Narrative of Lucy Ann Lobdell, the Female Hunter of Sullivan and Delaware Counties, N.Y.” Published under his birth name, Lobdell created what Boag calls an “early feminist tract” that juxtaposed hunting tales in New York and northern Pennsylvania with background of a short and abusive marriage (before be identified as a man) and the economic pressures on women:

“If she is willing to toil, give her wages equal with that of a man. And as in sorrow she bears her own curse, (nay, indeed, she helps to bear a man’s burden also,) secure to her her rights, or permit her to wear the pants, and breathe the pure air of heaven, and you stay and be convinced at home with the children how pleasant a task it is to act the part that woman must act.” (161-162)

Lobdell traveled to the Minnesota Territory where no one knew his name or identity and he could live, as he later said, a “man in all that the name implies.” He settled first on the shore of Lake Minnetonka and later west to Meeker County and was soon right back at hunting and living a rugged, exciting life.

Lobdell’s neighbors quickly took a liking to him, calling him “good company” and a “hale fellow well met.” Life was good.

But it didn’t last.

In 1858 Lobdell’s female anatomy was discovered and he was arrested, charged with impersonating a man. It turned out that wearing men’s clothing or otherwise acting like a man was not illegal and Lobdell couldn’t be charged but his reputation in Minnesota was ruined. Ostracized and called a “Wild Woman,” local officials bought Lobdell a train ticket and forced him to go back east where he came from.

Though his time in the West was pretty short, Lobdell’s story doesn’t end there. After his return, Lobdell settled near Bethany in Wayne County, Pennsylvania. Living as a man (and no one here had any reason to suspect otherwise), he taught classes in singing and dancing, and could be found playing the fiddle at all the good parties. Popular with the ladies in town, Lobdell eventually won the heart of the daughter of a local lumber merchant and they were soon engaged.

But then, a out-of-town visitor recognized Lobdell from New York. He conspired to expose Lobdell and run him out of town, but Lodbell’s fiancee discovered the plan (and the identity of her bethrothed) and warned him in time. Lobdell was able to escape town unharmed, but was out of a home yet again.

At some point shortly after this episode (the historical record is vague), Lobdell met a woman named Marie Perry while they were both living in a New York almshouse (Lobdell was living as a woman again at this point to survive), and the two quickly bonded. They soon left the almshouse and were married in 1869. They roamed northeastern Pennsylvania, living in huts, caves, or any where they could be in peace, working odd jobs to get by. Over the years they were arrested for vagrancy (or for Lobdell impersonating a man) a few times, appearing in prison records in Honesdale and Stroudsburg.

Joseph and Marie did settle in Damascus, Pennsylvania for a while, and it was there 1879 that the papers mistakenly believed Lodbell died. The New York Times published a long obituary of Lobdell’s life of “thrilling adventure and privation,” calling him a “Modern Diana” for all his exploits in the wilderness.

But Lobdell was very much alive, the news of his death just a rumor. According to some sources, Lobdell wandered away from home, had a “maniacal attack,” and was committed to the Willard Asylum for the Insane in New York. At Willard, Lobdell’s life and relationship with Marie was documented by resident physician Dr. Peter Wise. Wise published his research in an 1883 article called “Case of Sexual Perversion,” one of the earliest studies on the subject and one of the first to use the term ‘lesbian’ to define a sexual relationship between women.

In the 19th century medical literature on homosexuality and transexuality were not differentiated from other so-called “sexual perversions.” In Wise’s research on Lobdell, the physician determined he was a “sexual invert,” a 19th century term for homosexuality that linked sexual preference to an inborn reversal of gender traits.

Decades later Lobdell died in obscurity at Binghamton State Hospital (for the “Chronically Insane”) in 1912. It doesn’t appear that any records from the institution are available for research, so there’s probably information on the last decades of Lobdell’s life that we just don’t know.

Wise did publish multiple articles about Lobdell later on, which were cited frequently and helped shape the views of a generation of sexologists’ understandings of cross-dressing, sexual inversions, and the medical dynamics of homosexuality.

Lobdell’s life, though it impacted so many and influenced much scientific thought, is largely forgotten today. Eventually the medical community, taking cues from Turner’s Frontier Thesis, determined that behaviors and sexual preferences like his were more products of frontier life than biology or personal choices. Just as Lobdell was banished from Minnesota, Boag writes, “American sexologists eliminated people with non-heteronormative sexualities, the cross-dresser representing the central figure among these, from the frontier myth they helped create.” (187)

Regardless of the spotty record of Lobdell’s experiences, we know he had a significant impact on his neighbors, community, and the medical establishment that can’t be understated. And despite the best attempts of the mythological Western past to erase people like Lobdell, his story remains a vivid illustrations of cross dressing and transexuality from this era.

The stories of the Springer Daughters, Georgie McRay, and Joseph Lobdell are all different in their own significant ways. But each of these Pennsylvanians are linked by one thing: their coverage in the press. Newspapers and other publications were the one place where accounts cross dressing, transexuality, and homosexuality could be written and shared widely.

The press treated cross dressers and sexual inverts as suspicious curiosities in the West, and certainly encouraged the poor treatment, harassment, and even jailing that frequently met people like Georgie McRay and Joseph Lobdell.

But the papers were informative in a positive way for readers back then, and even more so for historians today. “It wasn’t that this time and place was more open or accepting of trans people, but that it was more diffuse and unruly, which may have enabled more people to live according to their true identities,” Boag later said in an interview about “Redressing the West,” “My theory is that people who were transgender in the East could read these stories that gave a kind of validation to their lives,” he says. “They saw the West as a place where they could live and get jobs and carry on a life that they couldn’t have in the more congested East.” Having these accounts (thanks to Boag’s work) helps us have a much fuller and interesting picture of the West too.

This is definitely the case with the handful of Pennsylvanians we know about, and there were undoubtedly more who lived, worked, and traveled West too.

Are you sharing this post on Twitter? The stories of the three Pennsylvanian’s life styles was so interesting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! Hadn’t shared on social media yet (I don’t know what it is, I always get really self conscious sharing work of mine online that hasn’t been edited).

Glad to hear you found these stories interesting too, I got the book as a gift and was expecting to just read about the West, the PA connection was just a bonus! Its a really good read, and the author’s methodology is really good for tracking down family history that’s obscure or was distorted/written out of the record. Highly recommend.

LikeLike

I’m a bit confused by switching back and forth between two names for Lobdell: Robert and Joseph.

LikeLike

Thanks for reading and commenting. I wrote got Lobdell’s name mixed up when I was writing this apparently and didn’t catch that when I published the post. His name was JOSEPH, not Robert. I really appreciate you pointing this out so I could fix all these mistakes.

LikeLike