On August 5, 2019 I was fortunate to speak at the Society of American Archivists/Council of State Archivists annual meeting with my colleagues Margery Sly (Temple University), Sierra Green (Heinz History Center), and Bridget Malley (Western Pennsylvania History and Action Consortium) about collaborative approaches to preserving and sharing disability history in Pennsylvania. I ran out of time and had to cut my part short (we only had an hour!), so I’m sharing my full presentation here in the hopes that this could be useful to other archivists interested in doing more with the documentary record of disability in their own areas. If you’re working on a project let me know! I’d love to hear more about it.

Introduction

Pennsylvania has an incredibly long and broad history of disability. The state was the site of the first American mental institution- Philadelphia’s “Pennsylvania Hospital-” founded in the mid 18th century. It is the birthplace of many disability advocacy groups that have worked tirelessly to improve the lives of people with disabilities. Over the centuries Pennsylvanians have established scores of public and private institutions- schools for the blind, centers for people with intellectual disabilities, asylums, sanitariums, and hospitals- that have been home to so many people with disabilities as well.

Pennsylvania has also been the site of legal battles and scandals that have had dramatic impacts on the community far beyond state lines. There have been several scandals at Pennsylvania institutions for people with psychiatric and intellectual disabilities that gained widespread attention and resulted in major changes in how society views and treats people with disabilities. Pennhurst State School and Philadelphia State Hospital at Byberry are among the most infamous. Advocacy and disability rights groups in Pennsylvania have been at the forefront of legal challenges that changed law and disability policy in the state and beyond.

Pennsylvania’s distinct place in the historic struggle of people with disabilities to attain human and civil rights has spurred concerns amongst archives, advocacy groups, and individuals with disabilities to preserve this history and (more importantly) make sure it is accessible.

This is a critical time to preserve and share the records of disability history in Pennsylvania. In recent years our state government has closed several old and large institutions. Records documenting the lives of hundreds of thousands of institutionalized people with disabilities have become much more vulnerable and at-risk for loss. Similarly, Pennsylvanians who lived and worked in many state and private institutions, and people who were involved in disability rights work in the 20th century are growing older and we’re running out of time to document their experiences.

One thing I want to make absolutely clear is that up until fairly recently the records of disability history in Pennsylvania were neglected in many regards. The PA State Archives and others preserved these records on an ad hoc basis and as a result much of this history has been under-documented.

For many archives, our interest in preserving and sharing the documentary record of disability came as a direct result of interacting and working with individuals with disabilities and advocacy groups. Not only are we indebted to them, but I think we are obligated to be the best collaborative partners we can be moving forward.

These records are simply too important to neglect any longer, but archives can’t and shouldn’t do all the work on their own. Many of us are pursuing ongoing collaboration between other archives, advocacy groups, scholars, and others in Pennsylvania to undertake this important and timely work. Our overall goal has been to make sure the documentary record of disability is as inclusive and complete as possible, and that it is accessible in meaningful ways to the public (especially the disability community itself). Without collaboration this simply isn’t possible.

Our hope is that all of you can learn from our experiences and pursue your own collaborative relationships preserving and sharing the records from any historically marginalized or under-documented communities.

The Perspective of State Government

In Pennsylvania, like many other states, the history of disability is closely intertwined with the history of state government. In PA this has been true since the 18th century. Legislation and assistance programs at the state level have had dramatic impacts on the disability community. Interactions between individuals with disabilities, their families, and advocacy groups with state officials and agencies has created a vast documentary record.

As an acquisitions archivist at the Pennsylvania State Archives, I work closely with many of these types of disability-related records, especially the records of Pennsylvania’s state-run institutions- typically known as state hospitals and state centers. These facilities have been home to many thousands of people with physical, intellectual, and psychiatric disabilities. In the past few years, the Pennsylvania State Archives has focused on collecting records from these institutions and promoting their research use. We’ve made a lot of amazing progress, in large part because of successful collaborations large and small we’ve had with other repositories, advocacy groups, and government agencies.

Importance of State-Run Institutions to Disability History

The first state-run institution in Pennsylvania was the State Lunatic Hospital in Harrisburg, established in 1845. Since then, the state built and operated over 50 other institutions. So we’re talking about administrative records that can span over 100 years, and admission/discharge records and case files for hundreds of thousands of individuals who lived in these places.

There are currently six state hospitals still operating that serve Pennsylvanians with mental illnesses and psychiatric disabilities, and four state centers that serve Pennsylvanians with intellectual disabilities.

These institutions were at the heart of government policy that affected people with disabilities, and their staff were often heavily involved in advancing medical and social ideas about disability.

Advocacy and disability rights groups have a long history of involvement with state-run institutions, often times in battles to improve conditions for residents and even to close them down. Advocacy groups were often closely involved in major legislation and judicial decisions that impacted these institutions too.

Most importantly, the stories and experiences of people who were institutionalized in mental hospitals and centers is captured really well in the medical and patient records created at these places. Since many of these people were marginalized and often had little or no family, these records are often the only documentation of their lives. We cannot lose them.

Our challenges

By law, historically significant records from these state-run institutions are to transfer to the State Archives when they are no longer active. If the records were created by state government, the Pennsylvania History Code mandates only we can take them. So whether we like it or not, the State Archives has to be involved in most efforts to preserve and share Pennsylvania’s disability history.

This is a good thing! These records have amazing stories that are too important to miss out on. I’m really proud of all the work the State Archives has done in preserving these records and making them available to researchers.

But at the same time, being a government archives presents some significant challenges in our work with disability records. Because of certain state laws, policies, and limited resources we have limited collecting, access, and outreach capabilities.

Since these institutions are state-run facilities, all records they generate are state property and there are records retention schedules that tell staff which records should be sent to the State Archives. But records management is usually a low priority for staff, especially really old inactive records so its really up to the State Archives to find and transfer these records. If we’re not proactive odds are the records won’t survive. This is quite the challenge for us, because we have a small accessioning team and usually I’m the only archivist we can spare to for any kind of work with disability records besides standard reference work in our search room.

The geographic spread of these institutions (historically built in isolated areas purposefully to separate people with disabilities from society) also makes it difficult for the State Archives to monitor the records at each one, or to collect records from them regularly. Most of our institution collections were received when a facility closes and our staff were able to come out one time to collect everything historically significant we could find then. That strategy hasn’t worked well and there are a lot of important records that were lost or destroyed as a result from a number of institutions.

One of the other big challenges we face is the legal restrictions on access. In Pennsylvania, we’re bound by the state Mental Health Code, which heavily restricts all records containing mental health information from pretty much anyone who is not that individual or the executive of their estate in perpetuity. This has made it really hard for researchers and advocate groups to access these records

So, what do we do?

Collaboration is the Solution

By collaborating with others, we’ve been able to find partners who can help us overcome these weaknesses.

I’ve been trying to think of what would have been helpful for me to know as I was getting started collaborating with outside archives and groups. After some thought, I realized it was the actual relationship building that I struggled with the most. Without a firm, trusting relationship with our partners, none of the successes we’ve had would have been possible.

I’d like to share a few of these with you, and leave you with a few important lessons I’ve learned.

The State Archives Situation Before Collaboration

In the past, the PA State Archives generally kept other archives, advocates, and government agencies at arms length. When we interacted with any of these groups it was just as a routine business sort of thing, we viewed them primarily as records creators and research patrons.

The State Archives had a poor reputation amongst advocacy groups and the genealogical community as a place that was difficult to navigate and wasn’t taking adequate steps to preserve the records of state mental institutions. The online mental institution wiki “Asylum Project’s” message board contains the following statements about records from several Pennsylvania institutions:

“there is probably a good chance that the records were left to rot by the state in some forgotten record room.”

“even active hospitals seem to ‘lose’ records by leaving them behind in abandoned buildings…”

“I recall reading an interview with a former worker there who stated on numerous occasions that tons of records and outdated medical equipment was sealed and left in unused tunnels at the hospital.”

All of the records that these message writers were talking about were at the State Archives and described in our finding aids. But even though the records are safe in the archives, if no one knows they’re here then they’re inaccessible regardless of any steps we take to preserve and describe them.

The State Archives really only went out to collect records if we got a call from an institution or if one closed. We mostly focused on administrative records and aggregate patient records like admission and discharge logs. There was a lot that we weren’t prioritizing, due to a lack of resources, because it didn’t fit in with out collection policies, and because we weren’t appraising it as valuable to move to the State Archives.

Since these were government records, no other repositories or advocacy groups could step in and collect them even if we weren’t.

I don’t want to give the impression that our situation was a disaster, but we were pretty content to go with the status quo and there was a whole lot more we could have been doing to meaningfully preserve and provide access to disability history in Pennsylvania.

Culture Change in the Archives Fosters Collaboration

A few years before I started working at the State Archives in 2016, we got a new director, David Carmicheal. When he came in, we had some restructuring and a culture change within our staff. We became much more proactive in record collecting, and more willing to work with outside partners to identify, preserve, and provide access to historical records in Pennsylvania, specifically government records.

Responsibility for non-reference interactions between the archives and outside groups was moved from our collections management staff to our accessioning and outreach section (which is where I work). Looking back, this was really useful since our accessioning staff had a more outward-looking perspective that could include all the historical records that were still out there and not just in our archives.

We started getting into earnest collaboration about 3 years ago, right around when I was hired. After hearing about some of the advocacy groups in Western Pennsylvania and their interest in Polk Center (an institution for children with intellectual disabilities in Northwest PA), we traveled out there to inventory their records and speak with staff about their records management responsibilities. When we arrived, we learned that that were a number of archival and advocacy groups that visited Polk recently and seemed interested in collecting their materials. Since it seemed like the State Archives was neglecting these important records, they wanted to ensure that these important records were preserved.

We could have contacted these groups, told them they cannot collect records from a government-run facility, and left it at that. But instead, we decided to use this as an opportunity to hold a big meeting and invite as many stakeholders from Pennsylvania advocacy groups, archives, and government offices that were involved in disability rights and advocacy as possible, let them know exactly what the State Archives does/collects, and invite everyone to work collaboratively to preserve and share the state’s disability history.

After that, we started collaborating with several archives, advocacy groups, and government offices that were represented at this meeting. The meeting didn’t put firm plans in place for specific projects, but it did help us start relationships that we were able to strengthen over the years and get tangible results. I’d like to talk about one success story from each of these three groups.

Collaborating with Government Agencies

One of our more successful collaborations with government agencies came at the same Polk Center that I mentioned above.

Following the big collaborative meeting, my accessioning team worked to get support from the leadership in the State Archives and the Department of Human Services (DHS, office that manages all state centers and hospitals)to travel to all institutions in the state that were still open to inventory their records and transfer anything we thought was appropriate for preservation at the State Archives. We had several follow-up meetings with them and explained how waiting until an institution closes risks many important records and that we need the support from them in order to make sure we get everything. Fortunately they agreed.

Our next step was to have our staff travel out to the institutions to survey and collect records. To help us with introductions and to get permission to move records, Secretary of Human Services wrote us a letter of introduction to all the State Centers explaining that the archives was working in collaboration with DHS and we had their full support to inventory and collect historical valuable records at each facility. I didn’t realize this at the time, but this letter made a huge difference in our work.

I already mentioned that the staff at Polk had been approached by several groups interested in preserving their records. They had taken care of these records for over a century and were weary about giving them to anybody else, even fellow government employees from the State Archives. Having a letter from their central office helped us get in the door and helped convince them to transfer records into our custody.

The Polk staff were also suspicious of outside groups who were advocate for institution abolition and wanted to collect records in order to expose Polk for being a harmful place for people with disabilities. They were extremely hesitant to give records to anyone they thought had particular motives for collecting records. After realizing this, we took time to explain exactly why were interested in their records, and that we wanted to collect records that shed light on all perspectives and voices from their facility.

Having the support of DHS, and building up a trusting relationship with these local staff members helped make them willing and even excited to have their historical records stored with us. We actually had such a good experience at Polk that their staff send me a Christmas card each winter. I’d call that a success! There is still more material we’re going to get from them in later accretions and with our healthy relationship we know that this won’t be a problem in the future.

Since then we’ve visited 10 other institutions in Pennsylvania and collected close to 300 cubic feet worth of material that are already getting heavy use from our patrons. We’ve built up a network of institutional staff who are interested in and knowledgeable about their records who work with us to preserve everything that’s valuable, and to keep an eye our for records that walked off from the institutions in the past and are out in non-government custody. There was a massive collection of early 20th century glass plate negatives from Polk that the hospital sold in a surplus supply auction in the 1990s that one staff member bought back decades later and thankfully donated to the archives. We suspect there are many, many other records out there and we’re relying on our government collaborators to help us recover them.

Collaborating with Advocacy Groups

There are a lot of advocacy groups working to improve disability rights and celebrate the history of people with disabilities in Pennsylvania. Since the Pennsylvania State Archives doesn’t have a robust outreach or education programs, having good relationships with these groups and working with them to promote the use of archival disability collections is vital.

One advocacy group we’ve had a lot of success is the Pennhurst Memorial and Preservation Alliance (PMPA), an organization founded in 2010 to preserve the memory of Pennhurst Center, an eastern PA institution for children with intellectual disabilities that was opened in the early 20th century and was closed by Supreme Court order in 1986 for dangerous and abusive conditions.

I first met a few of their board members last year at a Mid Atlantic Regional Archives conference session on disability history in Pennsylvania. After the session I was speaking with one of their Vice President and I mentioned we had recently transferred a large collection of Pennhurst patient files to the State Archives from their previous location in a condemned DHS storage building in Norristown, PA. I thought he’d be happy to hear that we had gotten these important records out of a poor environment, but he was actually a little upset. He was afraid that since these records were now at the State Archives, no one would ever be able to access them again. To him, keeping records in a bad place was better than the archives! Our reputation as a place with difficult barriers to access had made an impression on him.

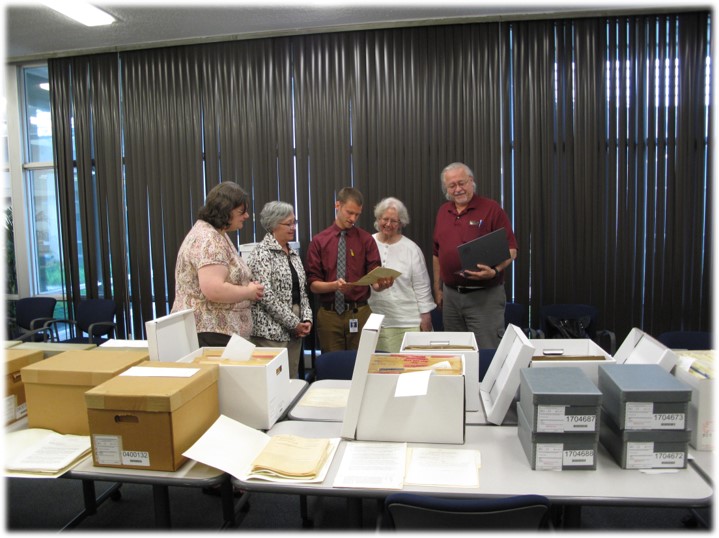

After that I emailed the entire PMPA board and invited them to visit the State Archives and see the Pennhurst records in their new boxes and folders, and to explain exactly what our access policies are. They thankfully came a few months later and they got a tour of the archives where we were able to show them how we care for records, and then I let them spend the afternoon looking through all our Pennhurst records.

I didn’t plan it, but they were looking through a box of the earliest patient records and found the records of Pennhurst’s very first resident, which had been accidentally misfiled decades ago and presumed lost. We were all really excited about this discovery, and I think this really helped build trust between the archives and the PMPA. Inviting them over and letting them look at the records also helped spur a long collaboration that is still going on now.

The PMPA gets a lot of inquiries about Pennhurst history and they now include us, connecting potential researchers with the State Archives. I don’t think many of them would have found us without the PMPA’s help, and that wouldn’t have happened if we didn’t have this trusting relationship.

One of PMPA’s board members, Mary Schreiner (Professor of Special Education at Alvernia University), came back as a researcher later that summer to look at admission files as part of a project to create life stories of patients from different decades. She used our non-restricted records and patient files with mental health information redacted to create narratives about who these people were and what they were like. When she finished writing these “Lives Remembered” narratives, she hired local members of the disability community and self advocates to read them out loud and will be making the recordings available online.

After her successful pilot project in 2018, we encouraged her to apply for our summer scholar in residence program the following summer. She did and was accepted! She will finish her project in August 2019, which expanded into documenting the lives of about 20 more Pennhurst residents.

One of the reasons I’m so excited about collaborating on this project with Mary was that it involved actual members of the disability community and was designed to be accessible to an audience with a wide range of disabilities.

We are really excited about this project and that we’ve been able to have Mary use these records in this way. In the 8 weeks that she’s been here so far, she’s also been helping better describe our Pennhurst records, sat in on a reference interview with me and an incoming disability history PHD student to advise him on research plans, and is working on two articles for a popular and an academic history journal about Pennhurst’s history. I am confident that all of these will raise the profile of these important records and lead to more researchers soon.

Working with the Pennhurst Alliance and other advocacy groups has been a great way to promote our collections, and to help repair the poor reputation that the State Archives had in the past.

Collaborating with Other Archives

Another challenge we face in the state archives is a rigid collection policy. Our collecting is bound by state retentions schedules. This makes it pretty simple for us to acquire records that are designated archival (which is decided partly by us and partly by state agency staff), but more difficult to collect records that do not have this designation.

We’re also very limited in our collection of non-government records, even though this is such a vital part of the history of disability. Records from family members, professional organizations that staff belonged, records from the media, and from advocacy groups who were closely monitoring their conditions are all necessary to get the entire picture. But we often times can’t collect them at the State Archives.

We ran into this issue when we were collecting records from Polk Center. We came across a collection of over 20,000 financial receipts that were created between 1903 and 1914. We had never seen anything like this before, most institutions would have destroyed these records long ago. They were squirreled away in a cabinet and forgotten about until our inventory.

This was an amazing collection that could be used to recreate day-to-day life for staff and residents at Polk, since it contained itemized listings of exactly what was being purchased and from whom in each transaction. It was a fantastic find!

However, these records were scheduled as “routine financial receipts” that were not archival and were to be destroyed after 3 years on our retention schedule. I knew that this was a special circumstance, but our archives collection committee ultimately decided to follow the records schedule and not make an exception for the receipts. But, I asked if we could offer them to another archives since we were not interested in them. Even though this was highly unusual (allowing a non-government repository to store public records) it was thankfully approved by our leadership.

I immediately thought of the Heinz History Center. They were one of the groups interested in Polk History that I mentioned earlier, and I knew that they had more freedom in their collecting policy. I also knew their archivist Sierra Green pretty well at that point and knew that she was also passionate about preserving and sharing the history disability and thought she would be a great advocate for Heinz taking the collection.

It was a little awkward at first trying to convince Heinz that this was an important collection worth taking since we were passing it up. So we had several conversations and invited Sierra to come out and look at the collection and talk about it in person. After she was able to make a good report Heinz agreed to take the collection and we wrote an MOU stating that these were public records that had to be publicly available at Heinz, but that they could be permanently stored there.

Its really unusual for the state archives to allow government records to be stored by non-government repositories, but due to the importance of this collection and the fact that we had a good trusting relationship with Heinz we were able to protect it and make it more accessible to the public.

It also turned out that Heinz was a great place to have this collection, since they have staff and volunteers that are working to index the receipts. If it had come to the State Archives we would have processed it minimally, making it harder for patrons to use.

I think we were able to find success here because Sierra and I did a lot of the legwork and discussion on our own. We only needed to involve the leadership and legal staff at our archives for the final writing of our MOU. Collaborating individually at first, and then as entire institutions when needed made the whole process a lot smoother.

Our Goals Moving Forward

We want to continue finding and collecting all institutional records in Pennsylvania so that they’re protected and in an accessible place, especially the records of individuals who were living there.

We want to continue working with our partners to promote the use of our collections and to find more connections between what we have and what other repositories have

We want to continue finding other advocacy groups and collaborative partners, get them acquainted with our collections and encourage them to use us for projects. I’d like to see us do more work with universities too. I’m inspired by a really interesting collaboration going on in North Carolina between the State Archives, UNC’s Community Histories Workshop, and the Dorthea Dix Park Conservancy Legacy Committee to digitize 19th century admission records and research the life stories of these people.

I’d also like to see other groups like the ARC of PA, the United Way, and the Western PA Disability History and Action Consortium see us as a resource and a partner

And lastly, our leadership recently decided to revise our access policies, and this will make to make records with mental health information easier for the public to access. I’ve already worked with Mary Schreiner on this a bit, and we’re hoping to get more feedback and advice from our collaborative partners on how to implement this new policy, and are hoping to lean on them for support promoting this in the future.

Most Important Lessons Learned

Looking back on the three years I’ve worked on collaborating with other groups to preserve and share disability history, these are some of the things I’ve found most useful:

-Trust is the most important part of any collaborative relationship. Period.

-Collaborations begin before projects and last long after they’re finished. Its not just about “getting down to business”

-Starting out small, even 1-1, can lead to more meaningful results.

-Remember that you represent your entire government/organization and that reputation can impact your relationships.

-Empower staff to pursue relationships independently.

-Support collaborative partners with your existing programs if you don’t have resources to dedicate to new projects.

What is Important to Collaborators?

And lastly, I sat down with our Pennhurst Alliance friend Mary Schreiner the other day and asked her what was most important to our collaborating relationship from her perspective. This is what she shared with me:

-Personal enthusiasm from staff.

-Making a “commitment to involving us” in this work that we’re doing at the archives.

-Understanding different motives of advocates (different organizations and different individuals) so we can trust and communicate with each other.

-Encouraging advocates to share/publish their collaborative work with archives.

-Be a sounding board for advocates’ projects and ideas.

.Make sure everyone knows “we trust you, we want you to be here”

-Social time is important, spend non-project related time with advocates too.

Conclusion

Collaboration has been essential to our collective work preserving and sharing disability history in Pennsylvania. And I think much of our success resulted from the trusting relationships that we built before we began collaborating on any specific projects.

Leave a comment